Updates to OIG’s Permissive Exclusion Authority

The Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) published updated criteria to its permissive exclusion authority under § 1128(b)(7) of the Social Security Act (the Act) (42 USC § 1320a-7(b)(7)). The guidance—published in mid-April and available here—introduced an OIG “risk spectrum” and several factors the Agency will weigh in determining whether to implement one of its several administrative remedies for those individuals or entities that defraud Federal health care programs.

Section 1128(b)(7) of the Act subjects individuals or entities to either mandatory or permissive exclusion from participating in Federal health care programs. Individuals or entities must be excluded for at least five years if they are convicted of crimes related to Medicare or Medicaid, patient abuse, felony health care fraud conviction, or felony controlled substances conviction (§ 1128(a)). Permissive exclusion, on the other hand, subjects those individuals or entities to the OIG’s discretion and covers, for example, entities controlled by an excluded individual or individuals or entities violating the Civil Monetary Penalties or anti-kickback statutes.

The publication—titled “Criteria for implementing section 1128(b)(7)”—updates the OIG’s position on exercising its permissive exclusion authority. The document replaces OIG guidance that is nearly 20-years old. Under the updated guidance, the OIG states that it presumes that a certain period of exclusion from participation in these Federal health care programs should be imposed on any person that defrauds Medicare, Medicaid, or any Federal health care program. From here, it is the individual or entity’s responsibility that is the subject of this exclusion to demonstrate that they shouldn’t be excluded; persons defrauding Federal health care programs will be excluded unless they can demonstrate otherwise.

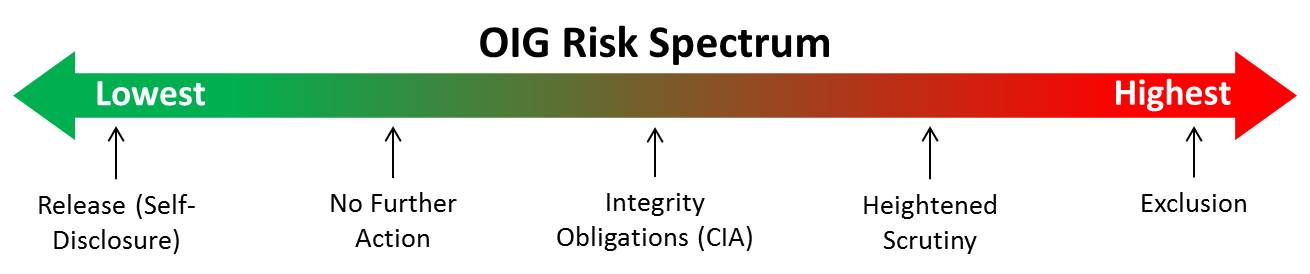

The OIG has several tools at its disposal ranging from releasing the person from its permissive exclusion authority under § 1128(b)(7) to exclusion. These are reserved for those deemed to be the lowest risk and highest risk, respectively. It also utilizes several intermediary sanctions depending on the perceived future risk. Together these comprise the “risk spectrum” introduced in the new guidance. Ranging from least to most severe, these include (1) release (self-disclosure); (2) no further action; (3) a Corporate Integrity Agreement (i.e., integrity obligations); (4) heightened scrutiny; and (5) exclusion. The OIG’s risk spectrum appears below.

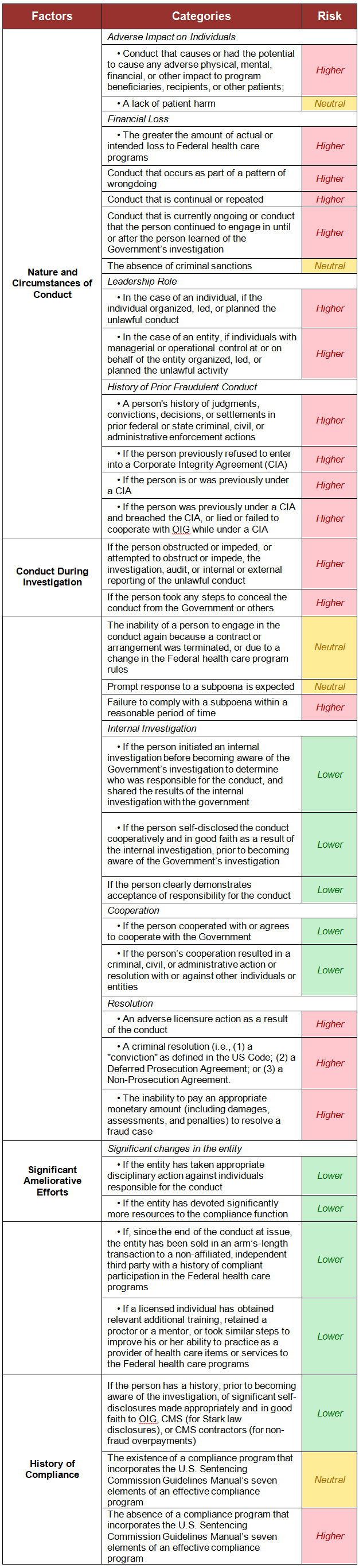

To assist where an individual or entity falls on the “risk spectrum,” the OIG considers several “non-binding factors” to weigh facts or circumstances to assist in determining the ultimate outcome. These facts or circumstances may include: consideration of whether or not the conduct was self-disclosed prior to a Government investigation, an entity’s conduct in assisting in a Government investigation or the speed an entity or individual responded to a subpoena. The OIG divides these factors into four categories with corresponding subfactors. The overarching categories include (1) nature and circumstances of the conduct; (2) conduct during the investigation; (3) significant ameliorative efforts; and (4) history of compliance.

These overarching categories and the criteria the OIG will consider in its determination appear below. The third column (titled “Risk”) illustrates the OIG’s position if it considers the fact either higher risk, lower risk, or having no impact on its determination. Of note, under “History of Compliance,” it considers a compliance program that tracks the traditional seven elements from the U.S. Sentencing Commission as having a neutral impact on its determination. The existence of a compliance program will no longer push an individual or entity into the lower end of the risk spectrum. It’s clear from the progression and maturation of health care compliance programs that their existence and execution is now the norm.

These categories appear for the sake of convenience from the OIG’s “Criteria for implementing section 1128(b)(7)” document.

For rural providers, the OIG indicated that it will consider all factors in making its assessment. This includes considering “whether the person is a sole source of essential specialized items or services in a community or provides items or services for which there are no alternative or comparable sources.” It concluded that these factors will most likely include remedies that fall short of exclusion given the entity’s position in its community. Although significant for Critical Access Hospitals and providers of the same ilk, this doesn’t mean that they are completely immune from any hardships for avoiding exclusion. Heightened scrutiny (i.e., unilateral monitoring and assessment from the OIG) and CIAs and associated costs can easily reach into the hundreds of thousands of dollars each year and are often typically multi-year agreements.